One of the better jobs was delivering the Tulsa Daily Tribune to its subscribers in Caney. Being a paperboy meant “being your own boss” and “making however much money you wanted to make” – or so the “recruiter” said when he was looking for a new paperboy. Like many good build ups, it was partly true. A paperboy had no supervision. It was up to him to get his stack of papers every day and get them delivered to the subscribers in a reasonable length of time. Every Saturday the paperboy went from door to door at every house on his route and attempted to collect the subscription fee from his customers. On a good day he would be able to collect from about three-fourths of his customers. The others were either not at home, did not answer a knock on the door, or begged off, saying they did not have any money at the time and “come back later”.

The paperboy had to send about 90% of the money he collected to the newspaper office in Tulsa. The rest was his profit. It did not take many non-paying subscribers to completely destroy a paperboy’s profits for a week. While it was true that he could increase his income by getting new customers it was also a fact that most of the people who wanted a paper delivered had long since been signed up. The others preferred to remain uninformed, or to get their news from a rival paper.

Paperboys did not get “hired” for this job. We were not considered employees of the Tulsa Tribune. We became what are now called an Independent Contractor, but such distinctions did not exist in those wondrous days before litigation became an American pastime. Before being given a paper route we had to pass a few hurdles. First, we had to have a bicycle. Then we had to persuade one of our neighbors to sign a form that said, in so many words, we were a dependable kid. Next we had to wheedle our dad into signing a form that said he would pay the paper bill if his son did not pay it in a reasonable length of time. That always led to a serious father-son conversation about dependability and initiative. A week’s paper bill was no small amount of money for the dad of any kid who wanted a paper route.

I jumped the hurdles sometime in my pre-teen years and was given a huge canvas bag that hung over my shoulder and down, practically to my knee’s, and a pocket sized book that had the names and addresses of all the customers on my route. The bag was to carry the newspapers I would deliver and the book was a simple ledger to be used on collection day. The retiring paper boy took a couple of days to show me the ropes, and then I was left on my own.

I soon discovered the meaning of the post office slogan, “Through sleet and snow, the mail will go”. It applied equally to the delivery of newspapers back in those pre-television days. People craved their daily paper. No matter what the weather, each day I arrived at the Santa Fe depot to meet the 4:15 train from Tulsa from which my papers would be thrown off onto the station platform. Since each paperboy’s route encompassed the entire town from border to border, east to west and north to south we needed to fold the papers in such a way that we could throw the paper onto our customer’s porch without slowing down as we pedaled past their house.

Folding was the first step in getting the papers delivered and we had to be quick about it. Our customers knew when the paper arrived and they wanted it soon after. Paperboys learned how to turn the flat paper into a compact little missile that they could throw accurately. Ordinarily it was easy to do and took only a few seconds per paper. On days when the paper was filled with ads it took hammer blows with our fists to beat the thick newspaper into a throwable shape.

Stopping, getting off our bikes and carrying the paper to the front porch would take too much time, but throwing the paper carelessly or inaccurately so that it landed in the shrubbery, under the porch, or too far out in the yard, led to complaints on collection day. Speed had to be balanced with accuracy. A few customers insisted that we put their paper inside their screened-in porch or between their screen door and the front door. With much grumbling about crabby and fussy adults, we had to accommodate them. If we did not our supervisor down in Tulsa would hear about it. When that happened we would find a terse, threatening note tucked inside the paper bundle that was tossed off the train.

All considered, paper routes were a pleasant way to earn a little money and having one led to my first step up from getting around on a bicycle. After a few months of being a paperboy I launched a campaign to convince Dad that since my route took in the entire town of Caney, I needed something faster than a bicycle. I had seen a few homemade contraptions that consisted of a little gasoline engine mounted on a bicycle. Crude as they were, they were faster and took a less effort than pedaling a bike.

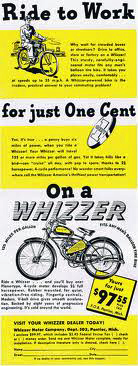

I looked upon Dad as a mechanical marvel and knew he could make one if he wanted to. He had a welding outfit and a blacksmith forge in his garage and was good with his hands. I had the bicycle, and little gasoline engines were cheap. I wheedled and cajoled, asking him to make my bike into a homemade motorbike, but he resisted. Then out of the blue, one Saturday afternoon Dad came home from a shopping trip to Coffeyville carrying a large cardboard box with the word “WHIZZER” written on it. Inside the box was a small engine, a gas tank with a decal that read “Whizzer” on each side, a large pulley to attach to the bikes rear wheel, a couple of cables and a little bit of hardware. Within a couple of hours Dad had it installed on my bike and I went “whizzing” down Spring Street towards town. I was ecstatic with pleasure. I was soon able to finish my paper route much faster, but with considerably less accuracy in hitting front porches with the folded paper.

The Whizzer was a nice little machine with a top speed of about 30-mph. It had an ingenious mechanism to start the engine. Mounted on the bike’s handlebars were two levers. One was the throttle; the other lever did something that more or less disconnected the engine which made the bike easy to pedal. I started the Whizzer by pedaling the bike normally until it was going at a fairly good clip. Then I pushed the “do something” lever, and the engine caught the beat and began putt putting, “whizzing” me and the bicycle down the street.